The Baillie Gate at the British Residency which was subjected to some of the heaviest fire.

India’s history holds many ghosts. It is a land of old loves, ancient hatreds, tarnished dreams and fleeting glory. There are tales of tragedy, and tales of heroism. I am in Lucknow in North India, and I am drawn into a haunting story of courage in the face of insurmountable odds.

Lucknow was once ruled by the Nawabs of Oudh, until the British in the guise of the East India Company, removed the last ruler, Wajid Ali Shah whose profligacy outraged their sense of Victorian morality. The Province was of strategic importance to the Brits, and disregarding the fact that the Nawab was also a cultured nobleman and generous patron of the arts, his extravagant lifestyle provided a convenient excuse to take over the state.

It was a measure that they would regret.

The annexation of Oudh was just one of the many factors, which ignited the tinderbox of rebellion in 1857 and brought about the Great Indian Mutiny—now called The First War of Independence by Indian nationals. Insurrection had already broken out in other parts of the country, and Sir Henry Lawrence, the Chief Commissioner, prudently moved British and Anglo-Indian civilians (my great-grandmother among them) into the 60-acre British Residency in June 1857.

Today, 150 years later, I sit under a tamarind tree, on a bench bordering the lawns of the old Residency, listening to the drone of bees, and the harsh cawing of crows. The sunlight throws dancing specks of light through the leaves of my sheltering tree, dust devils whirl briefly in the warm breeze along the unpaved pathways, and the air carries the scent of marigold flowers. If I’d been here in June 1857, these sounds would have been drowned by the bursting of shells, the acrid smell of gunpowder, and the almost continuous bombardment of cannon. The surroundings would have been shrouded in the grey dust of crumbling masonry.

The main Residency tower and building complex

Within the buildings surrounding me today, was a defensive army of about 850 British officers and soldiers, backed by about 700 loyal native sepoys, and around 150 civilian volunteers. But also within these grounds were several hundred women and children, all of them huddled into a warren of underground rooms in the “Tykhana” or women’s quarters.

The Tykhana

As I walk into the cramped Tykhana today, it is as if the place still holds the shadows of women soothing the fevers of dying children, stanching bloody wounds and bandaging torn limbs—while cringing at the whine of bullets and the heavy crash of cannonballs, slamming against the walls of their embattled shelter. The searing heat of that year’s June gave way to torrential monsoon rains, and with them came renewed outbreaks of typhoid, cholera, malaria and dysentery. The rooms, even today, carry the miasma of death.

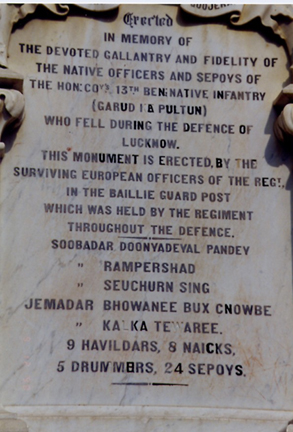

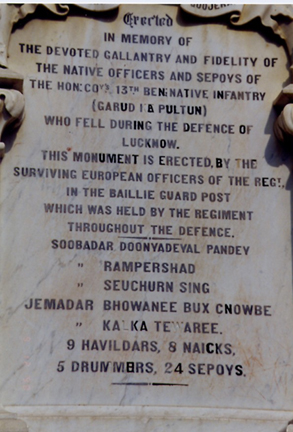

Two ant-sized visitors survey the view from the Residency tower

Emerging into the sunlight, I am glad to be free of the claustrophobic weight of so much sorrow—yet there are other reminders scattered throughout the Residency. The splendid ballroom, converted into a hospital, bears the scars of shellfire. A few residences still stand, their mildew-covered walls like rotted teeth lying open to the sky. A commemorative pillar erected by the British in heartfelt gratitude, pays tribute to the courage of Indian sepoys—many of them Sikhs—who defended the Residency alongside their British compatriots. Without their unswerving loyalty, the small English army contingent could not have held out against the rebels.

Commemorative monument

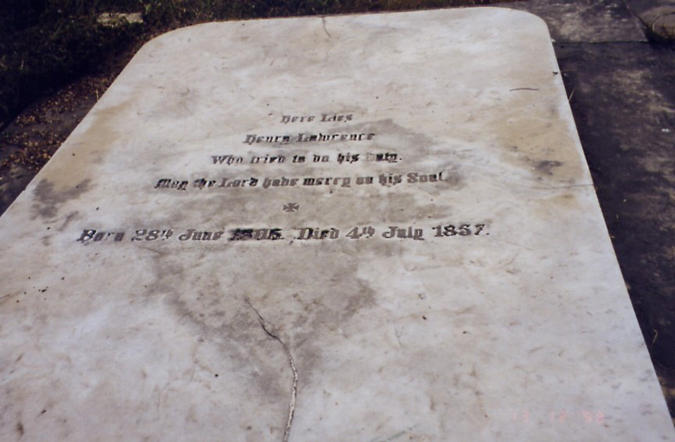

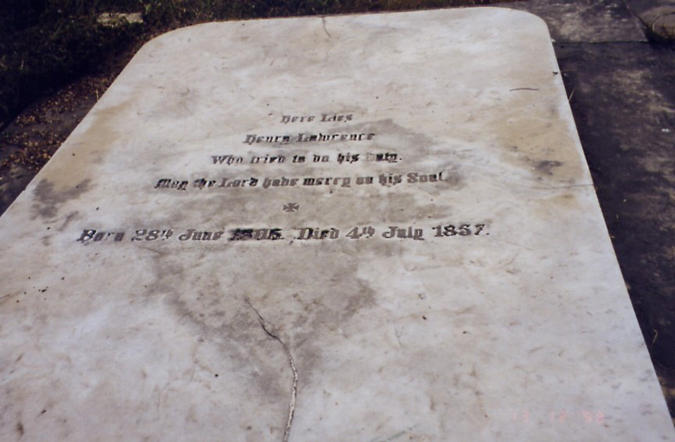

The cemetery headstones tell their own tales of loss and bereavement. Sir Henry Lawrence valiant to the end, was killed in the early days of the Mutiny, and his grave in the cemetery honours his last whispered request, “Put on my tomb only this: ‘Here lies Henry Lawrence, who tried to do his duty. May the Lord have mercy on his soul.’”

Sir Henry Lawrence's Tombstone |

In appreciation of their loyalty |

It would be 141 days before Sir Colin Campbell and his Highland battalion backed by other army detachments, came to the rescue of the besieged occupants of the Residency on November 17th. Only 800 soldiers and non-combatants, along with about 550 ragged and painfully emaciated women and children survived the ordeal.

The conflagration of the Mutiny blazed across the Indo-Gangetic plain and the carnage on both sides left enduring scars of bitter mistrust. As a direct result of the uprising, the British government took over the reins of administration from the East India Company, and assumed full military, administrative and judicial powers over the nation. In 1858, India became Britain’s “fairest jewel in the Crown.”

La Martiniere Boys' School

Another legacy from the days of the Raj, is LaMartiniere Boys’ School—unquestionably one of the most unique educational institutions in the world. Set within fifty acres (part of which now forms a public golf course) the building is an extraordinary edifice, lavishly decorated with rampant lions, Grecian statuary, gargoyles and fluted colonnaded pillars. The ceiling and walls of chapel and its entrance hall are plastered in Wedgewood pink and blue motifs. Although a former Marquess, derisively labelled it “an over-embellished wedding cake” I think of it more kindly as a whimsical folly on a grand scale.

Blue and white Wedgewood style decoration in the Chapel Hall

Named “Constantia” it was built by a wealthy French mercenary, Major-General Claude Martin as a palace for himself and the women of his harem—accommodated in a bibi-khana (women’s residence) in an adjoining wing.

Old Lucknow has the ambience of a medieval Turkish city, filled with crumbling, yet once splendid Islamic mosques, tombs and mansions such as the romantically named “Dilkhusha Palace”(Heart’s Delight”). I dismount from my rickshaw near the magnificent Rumi Darwaza, a gateway, to the old city, to explore an extraordinary building built in 1784. The Bara Imambara (once the residence of an Imam, or religious leader), originally built as a famine relief project, is a marvel of architecture: its 15-metre high vaulted central hall stretches for 50 metres (the longest in the world) without any intermediary supporting pillars. And the acoustics are remarkable. My guide gently tears a piece of paper at the far end of the gallery and I hear the ripping sound on the opposite side of the hall.

Gateway into the Bara Imambara

Views from the terrace of the Bara Immambara |  |

The upper floor consists of labyrinthine passages, the “bhul-bhuliaya” and visitors are challenged to find their way out of the maze. Few succeed and guides are poised to come to the rescue. The acoustics here too are astonishing. A whisper against one wall can be picked up beyond several turns and twists of the corridors. Always suspicious of political and military conspiracies, this how the rulers of Lucknow guarded against disloyalty on the part of the keepers of the Imambara.

A corridor in the labyrinthine Bhul-bhuliya

Also within the Bara Imambara complex is a fine mosque, but it’s off-limits to non-Muslims, so I explore the baori instead. According to my guide, this is a well that is reputedly so deep as to be fathomless. He chucks a large stone in, and says, if I come back after a couple of hours, I just might be lucky enough to hear it hit the bottom!

Lucknow, like any other city, is, of course, much more than its historical monuments. The modern shopping area of Hazrat Gunj is blandly commercial with upscale shops and garish concrete buildings. By contrast, the narrow lanes of Aminabad bazaar in old Lucknow, seethe with colour and movement. Popular Bollywood film music blares out from small food kiosks, flower sellers offer marigold garlands, and fruit and vegetable stalls are piled high with produce. Cows amble through the crowds, unhindered by shoppers, and vice-versa. At a clothing store, I buy a strawberry pink cotton kurta (tunic) adorned with “chikkan” work—a type of shadow embroidery unique to Lucknow—for less than the cost of half a bag of groceries in Canada!

Read more...

There is not one dirty word in it, and it is funny.

There is not one dirty word in it, and it is funny.

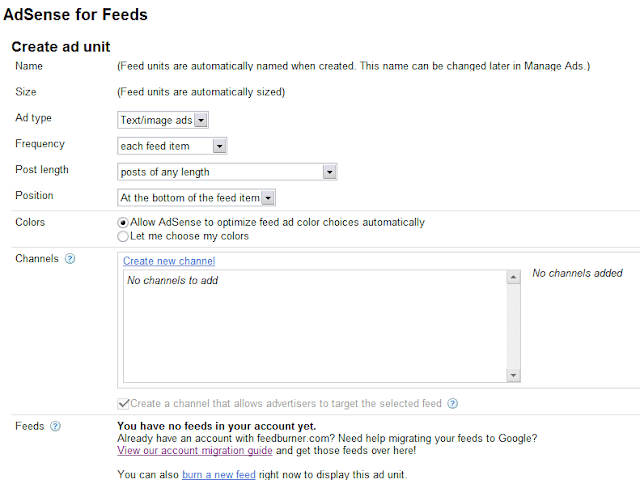

Presently, there is no connection between Adsense account and the Feedburner account .Therefore is is need to migrate from FeedBurner to Google Adsense.Google will soon provide a self-service process to migrate from an account on the original

Presently, there is no connection between Adsense account and the Feedburner account .Therefore is is need to migrate from FeedBurner to Google Adsense.Google will soon provide a self-service process to migrate from an account on the original